"Hunger Was a Good Discipline"

As we've established, food was a pleasurable part of Hemingway's life. Certainly, he enjoyed to indulge in rich food and drink, but the Paris years were also, surprisingly, peppered with physical hunger. In A Moveable Feast, he has a chapter entitled "Hunger Was a Good Discipline." Particularly in this chapter, Hemingway describes how he would regularly skip his afternoon meal, or lunch, in order to save money, specifically since he wasn't making much money as an American journalist in Paris. Hemingway describes the challenge of going hungry in a city with such enticing food, and that "all the bakery shops had such good things in the windows and people ate outside at tables on the sidewalks so that you saw and smelled the food" (59). In order to avoid these temptations, Hemingway devised a specific walking path in which he could avoid the most alluring enticements, and he argued that the Luxembourg gardens were the best spot for this since "you saw and smelled nothing to eat all the way from the Place de l'Observatoire to the rue de Vaugirard" (59).

Hemingway's details of his specific avoidance of food are humorous, and his descriptions of painstakingly dodging food is charming; the tone of the chapter is not one of sadness or wishing that he could eat an afternoon meal, but more of one in which he surprisingly relishes the opportunity to experience hunger. As he views paintings in an art museum, he details that "all the paintings were sharpened and clearer and more beautiful if you were belly-empty, hollow hungry" (59). Hemingway views hunger as almost a drug-like experience, in that "all of your perceptions were heightened again. The photographs looked different and you saw books that you had never seen before" (60).

Hemingway specifically describes admiring art by Cézanne, such as this here.

Coming from a man who infamously loved to eat, these conclusions are quite curious. To Hemingway, his avoidance of food became more than a money-saving mechanism, but a part of his image as an artist-- an image that was at least somewhat actually "starving." Just as Hemingway romanticized his experiences with food itself, he managed to romanticize the lack of it thereof, and how avoiding food allowed him to experience the world around him in a new, exciting way.

Although, towards the end of the chapter, Hemingway seems to be less keen on his idea of hunger, and after chatting with a friend, he caves to the desire to purchase himself a proper meal, and that he ordered a "distingue...potato salad, pommes a huile, and a cervelas...oil and bread...and a demi" (62). As his resistance fades, Hemingway does not only purchase a meal, but one of extravagance and decadence. Additionally, he moves to resign himself to making more money so that he, alongside his wife and child, could eat better as a whole.

Overall, Hemingway's experience with hunger seems somewhat arbitrary; if he can easily appease his hunger when he decides to deal with hunger no more, then how necessary is his plight with hunger at all? Again, this reinforces the idea that hunger is more of a romantic ideal to Hemingway than anything; his abstinence from food, as much as his enjoyment of it, makes him feel closer to his craft, and more fully able to experience the works of other artists. Overall, Hemingway's "hunger" seems somewhat indulgent, considering that many who do face hunger do not do so when they have the option to appease it, as he is able to easily solve his with a resolution to produce more regular content as a journalist.

For Hemingway, being hungry was another avenue of adventure-- one that contrasted with his other obsession of actually tasting and experiencing rich food and drink. Hunger as a "discipline" for Hemingway does not seem to have been a form of punishment, but rather, one of the many ways in which he pushed his body to feel alive, and to keep himself from the monotony and tedium of what might have been the everyday.

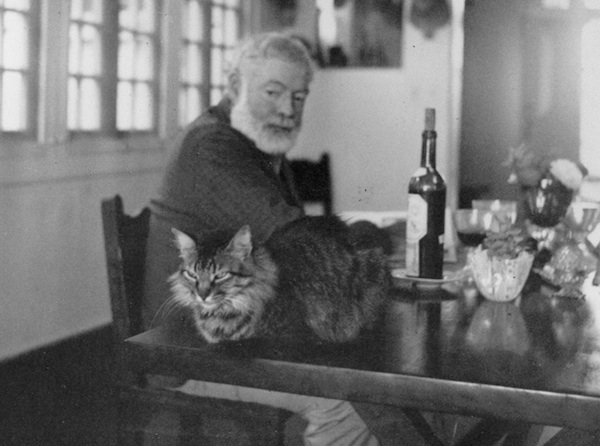

Photo from here.

Hemingway's details of his specific avoidance of food are humorous, and his descriptions of painstakingly dodging food is charming; the tone of the chapter is not one of sadness or wishing that he could eat an afternoon meal, but more of one in which he surprisingly relishes the opportunity to experience hunger. As he views paintings in an art museum, he details that "all the paintings were sharpened and clearer and more beautiful if you were belly-empty, hollow hungry" (59). Hemingway views hunger as almost a drug-like experience, in that "all of your perceptions were heightened again. The photographs looked different and you saw books that you had never seen before" (60).

Hemingway specifically describes admiring art by Cézanne, such as this here.

Coming from a man who infamously loved to eat, these conclusions are quite curious. To Hemingway, his avoidance of food became more than a money-saving mechanism, but a part of his image as an artist-- an image that was at least somewhat actually "starving." Just as Hemingway romanticized his experiences with food itself, he managed to romanticize the lack of it thereof, and how avoiding food allowed him to experience the world around him in a new, exciting way.

Although, towards the end of the chapter, Hemingway seems to be less keen on his idea of hunger, and after chatting with a friend, he caves to the desire to purchase himself a proper meal, and that he ordered a "distingue...potato salad, pommes a huile, and a cervelas...oil and bread...and a demi" (62). As his resistance fades, Hemingway does not only purchase a meal, but one of extravagance and decadence. Additionally, he moves to resign himself to making more money so that he, alongside his wife and child, could eat better as a whole.

Photo from here.

Overall, Hemingway's experience with hunger seems somewhat arbitrary; if he can easily appease his hunger when he decides to deal with hunger no more, then how necessary is his plight with hunger at all? Again, this reinforces the idea that hunger is more of a romantic ideal to Hemingway than anything; his abstinence from food, as much as his enjoyment of it, makes him feel closer to his craft, and more fully able to experience the works of other artists. Overall, Hemingway's "hunger" seems somewhat indulgent, considering that many who do face hunger do not do so when they have the option to appease it, as he is able to easily solve his with a resolution to produce more regular content as a journalist.

For Hemingway, being hungry was another avenue of adventure-- one that contrasted with his other obsession of actually tasting and experiencing rich food and drink. Hunger as a "discipline" for Hemingway does not seem to have been a form of punishment, but rather, one of the many ways in which he pushed his body to feel alive, and to keep himself from the monotony and tedium of what might have been the everyday.

Comments

Post a Comment