The Luxury of Camp Food

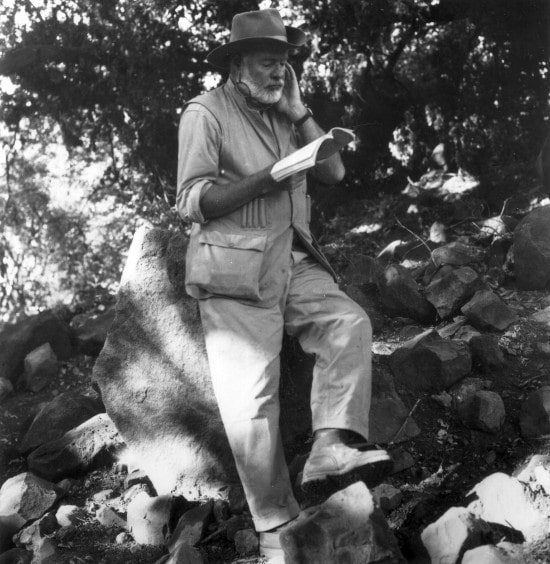

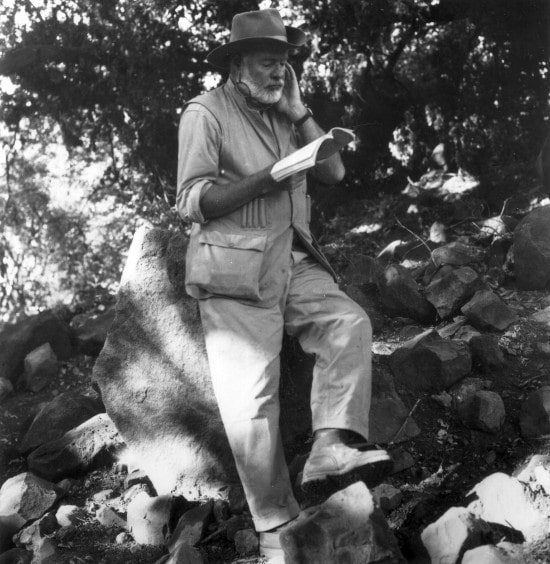

Amidst Hemingway's decadent descriptions of the opulent meals and cuisine of Paris and Europe, he was still, at his core, a man who appreciated the simple things of life. Infamously, he loved Paris and the city, but also, he was known for his dedication to camping and the great outdoors. Within The Nick Adams Stories, Hemingway captures the essence of unexplored wilderness and the glory of the American backpacking journey. Throughout the stories, readers are able to witness the trajectory of Adam's experiences from adolescence through adulthood, and how his experiences shape him as he matures.

In contrast with the flamboyance and glamor of the Paris years, The Nick Adams Stories capture a more rugged, back-to-roots approach, alongside an appreciation for the simplicity of nature. In The Hemingway Review, Neil Stubbs writes that

Particularly, within the collection of stories, "Big Two-Hearted River" details Adams's solo camping experience, in which he finds himself to be quite hungry after a day of hiking and exploring. After taking time to prepare his campsite, he thinks to himself that "He did not believe he had ever been hungrier" (184). Immediately afterwards, Adams begins to prepare a meal for himself of "a can of pork and beans and a can of spaghetti...tomato catchup and...four slices of bread" (184). Obviously, this meal is comprised of simple camping stables; non-perishables and canned goods that Adams was able to transport with him inside his pack-- quite different from meals of rich wines, mussels, and the like.

As Adams's hunger escalates, it is increasingly challenging for him to resist the meal that he has prepared for himself, but he restrains himself since "He knew that the beans and spaghetti were still too hot... he was not going to spoil it all by burning his tongue. For years he had never enjoyed fried bananas because he had never been able to wait for them to cool" (185). Adams' decision to wait to eat his food is one of a carefully controlled desire to relish the food, and not to taint it with the consequences that would result from impatience.

Additionally, Adams carefully describes the process of preparing the food; although he does look forward to eating the meal soon, he also enjoys the steps of compiling the meal. Hemingway describes the process of the food cooking and how "He poured about half the contents out into the tin plate. It spread slowly on the plate... He poured some tomato catchup... All right. He took a full spoonful from the plate" (184-185). Overall, the process leading up to the eating is part of the eating itself; the small details and elements of preparing the food as a whole builds Adams's anticipation and enjoyment of the food, and he, between joyful mouthfuls, murmurs "Chrise... Geezus Chrise" (185).

As a whole, camp food has just as much appeal to a young Hemingway as did the feats of Parisian cuisine, and it seems that much of it results from the process of the preparation, and the culmination of the completed meal. When in the great outdoors, Adams, or Hemingway, earned his food, and as a result, he seemed to enjoy it all the more, accompanied only by his backpack and thoughts, establishing his own sort of land, place, and territory in the world.

Works Cited:

Hemingway, Ernest. The Nick Adams Stories. Scribner, 1972.

Stubbs, N. "'Watch Out How that Eggs Runs': Hemingway and the Rhetoric of American Road Food." The Hemingway Review, vol. 22, no. 1, 2013, pp. 79-85. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/hem.2013.0033

Photo from here.

In contrast with the flamboyance and glamor of the Paris years, The Nick Adams Stories capture a more rugged, back-to-roots approach, alongside an appreciation for the simplicity of nature. In The Hemingway Review, Neil Stubbs writes that

"Before Hemingway's exposure to European cafe society, he was arguably an American natural, a self-style vagabond who rode the rails through northern Michigan to escape his parents' respectable suburban home. His travels on the highways and rail-roads of the United States instilled a love of Americana and a wanderlust that were lifelong qualities. Additionally, the young Hemingway (whose avatar is Nick Adams) valued the elemental experience of simple foods in unadorned and unpretentious settings" (80).In this way, food notably works throughout Hemingway's works to distinguish a time, era, and zeitgeist of the chapters of his varied life. Remarkably, within The Nick Adams Stories, Hemingway does this by utilizing Nick Adams as a stand-in for himself, and through his telegraphic prose and carefully selected details.

Particularly, within the collection of stories, "Big Two-Hearted River" details Adams's solo camping experience, in which he finds himself to be quite hungry after a day of hiking and exploring. After taking time to prepare his campsite, he thinks to himself that "He did not believe he had ever been hungrier" (184). Immediately afterwards, Adams begins to prepare a meal for himself of "a can of pork and beans and a can of spaghetti...tomato catchup and...four slices of bread" (184). Obviously, this meal is comprised of simple camping stables; non-perishables and canned goods that Adams was able to transport with him inside his pack-- quite different from meals of rich wines, mussels, and the like.

Photo from here.

As Adams's hunger escalates, it is increasingly challenging for him to resist the meal that he has prepared for himself, but he restrains himself since "He knew that the beans and spaghetti were still too hot... he was not going to spoil it all by burning his tongue. For years he had never enjoyed fried bananas because he had never been able to wait for them to cool" (185). Adams' decision to wait to eat his food is one of a carefully controlled desire to relish the food, and not to taint it with the consequences that would result from impatience.

Photo from here.

Additionally, Adams carefully describes the process of preparing the food; although he does look forward to eating the meal soon, he also enjoys the steps of compiling the meal. Hemingway describes the process of the food cooking and how "He poured about half the contents out into the tin plate. It spread slowly on the plate... He poured some tomato catchup... All right. He took a full spoonful from the plate" (184-185). Overall, the process leading up to the eating is part of the eating itself; the small details and elements of preparing the food as a whole builds Adams's anticipation and enjoyment of the food, and he, between joyful mouthfuls, murmurs "Chrise... Geezus Chrise" (185).

As a whole, camp food has just as much appeal to a young Hemingway as did the feats of Parisian cuisine, and it seems that much of it results from the process of the preparation, and the culmination of the completed meal. When in the great outdoors, Adams, or Hemingway, earned his food, and as a result, he seemed to enjoy it all the more, accompanied only by his backpack and thoughts, establishing his own sort of land, place, and territory in the world.

Photo from here.

Works Cited:

Hemingway, Ernest. The Nick Adams Stories. Scribner, 1972.

Stubbs, N. "'Watch Out How that Eggs Runs': Hemingway and the Rhetoric of American Road Food." The Hemingway Review, vol. 22, no. 1, 2013, pp. 79-85. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/hem.2013.0033

Comments

Post a Comment